A Personal Analysis from a Woman’s Perspective

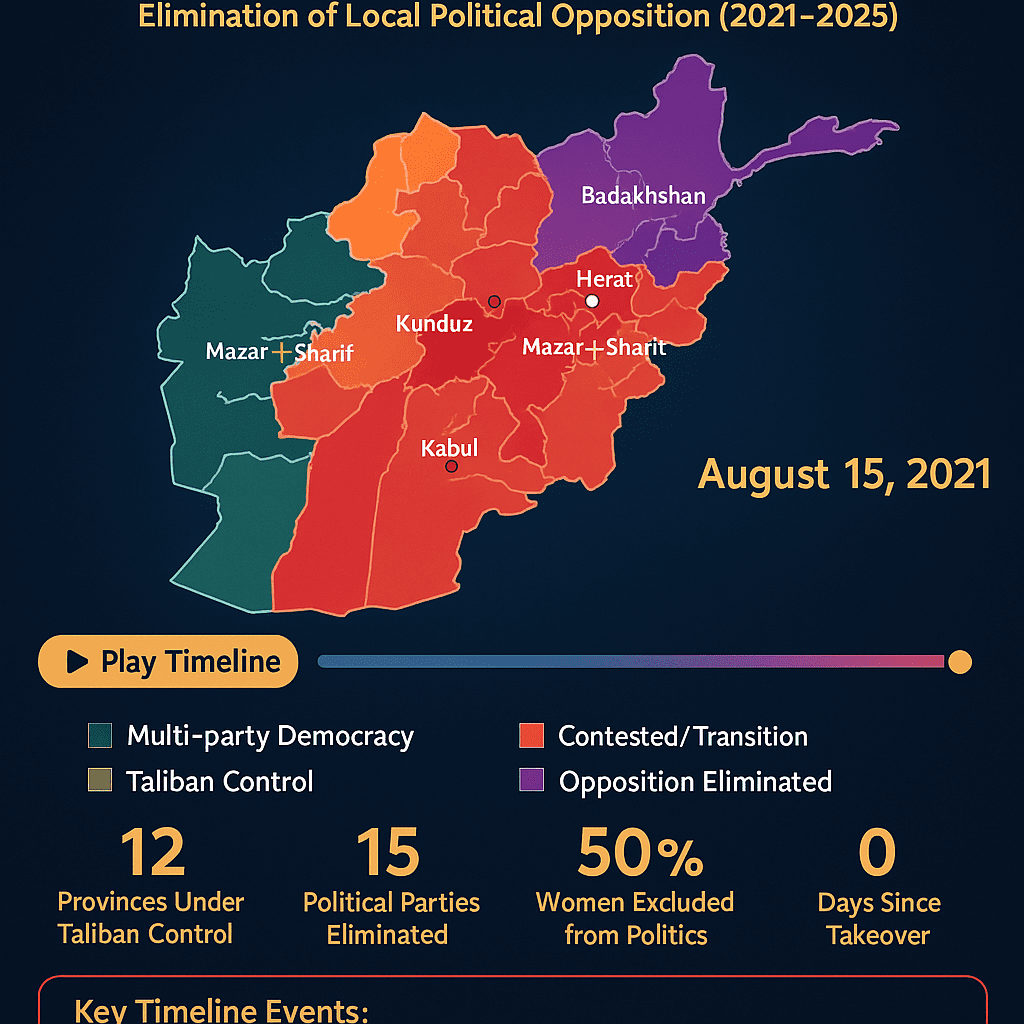

Since the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021, Afghanistan has witnessed unprecedented political restrictions that have fundamentally altered the nation’s landscape. Here’s a startling fact that keeps me awake at night: within just two years of Taliban rule, all political parties except the Taliban itself have been effectively banned or dissolved, marking one of the most complete political monopolisations in modern history! This is not a distant issue, but a pressing concern that demands our immediate attention.

As a woman witnessing Afghanistan under Taliban rule in 2025, I am deeply affected by the loss we have experienced. The systematic elimination of political opposition has not only excluded women like me from decision-making, but it has also extinguished the hope of diverse voices shaping Afghanistan’s future. This comprehensive analysis examines how these political party bans have reshaped Afghanistan’s political, social, and economic fabric, and what it means for millions of women and marginalised communities who once dared to dream of political participation.

The Complete Political Transformation of Afghanistan

When I think about Afghanistan’s political transformation, I’m reminded of watching a house of cards collapse in slow motion. The country’s multi-party system, which had been fragile yet functioning, was dismantled with surgical precision, leaving no room for opposition voices. This isn’t just a political change, but a personal loss for many of us.

Before August 2021, Afghanistan had a complex political ecosystem that, although imperfect, included various political parties representing diverse ethnic, tribal, and ideological interests. The National Assembly had 249 seats in the lower house and 102 in the upper house, with constitutionally mandated quotas ensuring women held at least 27% of parliamentary seats. As a woman, I find it particularly painful that these were among the first positions to be eliminated.

The timeline of political dissolution reads like a systematic purge:

- August 2021: Immediate dissolution of parliament and presidential system

- September 2021: Formation of an all-male interim government with no opposition representation

- October 2021: Formal announcement that political parties serve no purpose under Islamic governance

- 2022-2024: Systematic arrest and intimidation of former political leaders

- 2025: Complete consolidation with no recognised political opposition

What strikes me most is how different this feels from the previous Taliban rule (1996-2001). While that regime was also authoritarian, the current iteration seems more sophisticated in its elimination of political pluralism. They’ve learned from their past mistakes and created what appears to be a more permanent system of control.

Key political figures haven’t just been silenced—they’ve been forced into exile or worse. Former President Ashraf Ghani fled the country, while countless women politicians like Fawzia Koofi and Habiba Sarabi found themselves not just unemployed, but actively hunted. The personal stories behind these statistics haunt me because I know that in another life, any woman with political aspirations could have been in their shoes.

Taliban’s Governance Structure and Political Monopoly

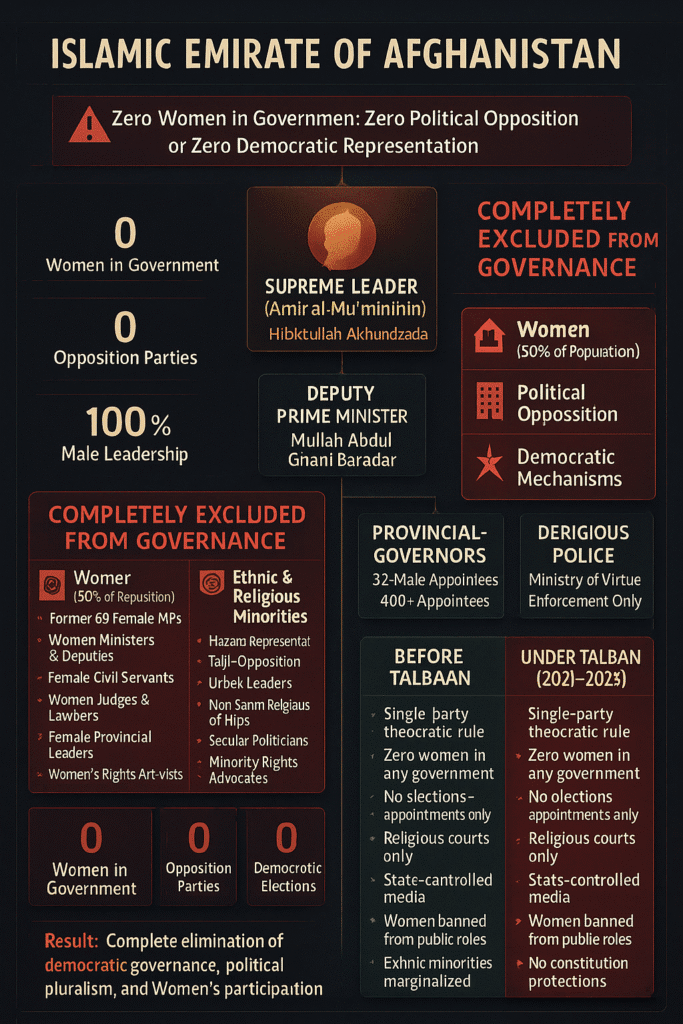

Understanding the Taliban’s governance structure requires looking beyond Western concepts of political organisation. What they’ve created isn’t just a single-party state—it’s something more fundamental: a theocratic monopoly that rejects the very idea of political opposition as un-Islamic.

The Islamic Emirate operates through a hierarchical system that places ultimate authority in the hands of the Supreme Leader, currently Hibatullah Akhundzada. Below him, various ministries and councils operate. Still, unlike traditional governmental structures, these positions are filled not through political processes but through religious and tribal hierarchies that explicitly exclude women and minorities.

What’s particularly troubling from my perspective as a woman is how this system institutionalises our exclusion. It’s not just that women can’t participate in politics—it’s that the very structure of governance is designed to ensure we never can. Religious councils, dominated by male clerics, have replaced elected bodies. Decision-making processes flow from religious interpretation rather than democratic representation. This not only undermines the principles of democracy but also severely restricts women’s rights and their ability to participate in shaping their own future.

The Taliban has skillfully integrated regional and tribal leaders into their governance model, but only those who align with their strict interpretation of Islamic law. This creates an appearance of inclusivity while maintaining absolute control. Local governors and administrators are chosen not for their political acumen or representative qualities, but for their loyalty to Taliban ideology and their willingness to enforce increasingly restrictive policies.

Impact on Civil Society and Democratic Institutions

The dissolution of democratic institutions hasn’t just changed how Afghanistan is governed—it has fundamentally altered what it means to be an Afghan citizen, particularly if you’re a woman or belong to a minority group.

When parliament was dissolved, Afghanistan lost more than a legislative body. We lost the dreams and aspirations of countless women who had fought for political representation. I think about women like Shukria Barakzai, who survived multiple assassination attempts to serve in parliament, only to see her life’s work erased overnight. The constitutional requirement that women hold 27% of parliamentary seats wasn’t just a number—it represented hope for millions of girls who could imagine themselves in positions of power.

Civil society organisations and NGOs have faced systematic dismantling. Women’s rights organisations, which once formed the backbone of civil society activism, have been banned outright. The Afghanistan Women’s Chamber of Commerce, which supported thousands of female entrepreneurs, was shuttered. Professional associations for women lawyers, doctors, and teachers have been dissolved.

The impact on education reveals the depth of this transformation. Student unions, debate societies, and political clubs on university campuses have been eliminated. Young women who once participated in model UN competitions or student government now face restrictions on even attending classes. The message is clear: political engagement, even at the most basic level, is not for women. This not only hinders their personal growth and development but also deprives the nation of potential future leaders and change-makers.

Media restrictions have created an information vacuum that makes organising opposition nearly impossible. Female journalists, who once comprised 20% of Afghanistan’s media workforce, have been banned from television and radio. Without independent media, documenting and resisting political oppression becomes exponentially more difficult.

International Response to Afghanistan’s Political Restrictions

The international community’s response to Afghanistan’s political party bans has been swift but, from my perspective as someone watching Afghan women suffer, frustratingly inadequate. While there have been condemnations and sanctions, the lack of coordinated action and the focus on geopolitical interests over human rights have left many of us feeling abandoned and unheard.

The United Nations has consistently condemned the elimination of political pluralism, with the UN Special Rapporteur on Afghanistan regularly highlighting how political restrictions violate fundamental human rights. However, these condemnations feel hollow when women continue to disappear from public life entirely. The UN’s own meetings about Afghanistan often feature all-male panels discussing women’s rights—an irony that isn’t lost on those of us advocating for inclusion.

Diplomatic isolation has been the primary tool of international pressure. No country has formally recognised the Taliban government, and Afghanistan’s seat at the UN remains officially vacant. While this sends a strong message about international standards, it also means that Afghan women have no formal channels to advocate for their rights on the global stage.

Economic sanctions have created a complex dynamic. While intended to pressure the Taliban toward political inclusion, these measures often harm ordinary Afghans—particularly women who were already economically marginalised—more than they impact Taliban leadership. The freezing of Afghanistan’s foreign reserves has crippled the economy, but hasn’t led to meaningful political reforms.

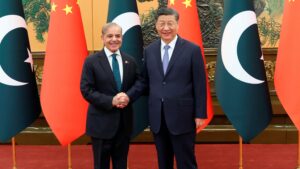

Regional powers have taken varied approaches that reflect their own strategic interests rather than concern for Afghan women’s rights. Pakistan has maintained close ties while publicly calling for inclusion. Iran has engaged pragmatically while privately expressing concern about minority rights. China and Russia have moved toward informal recognition, prioritising economic and security interests over political pluralism.

Economic Consequences of Single-Party Rule

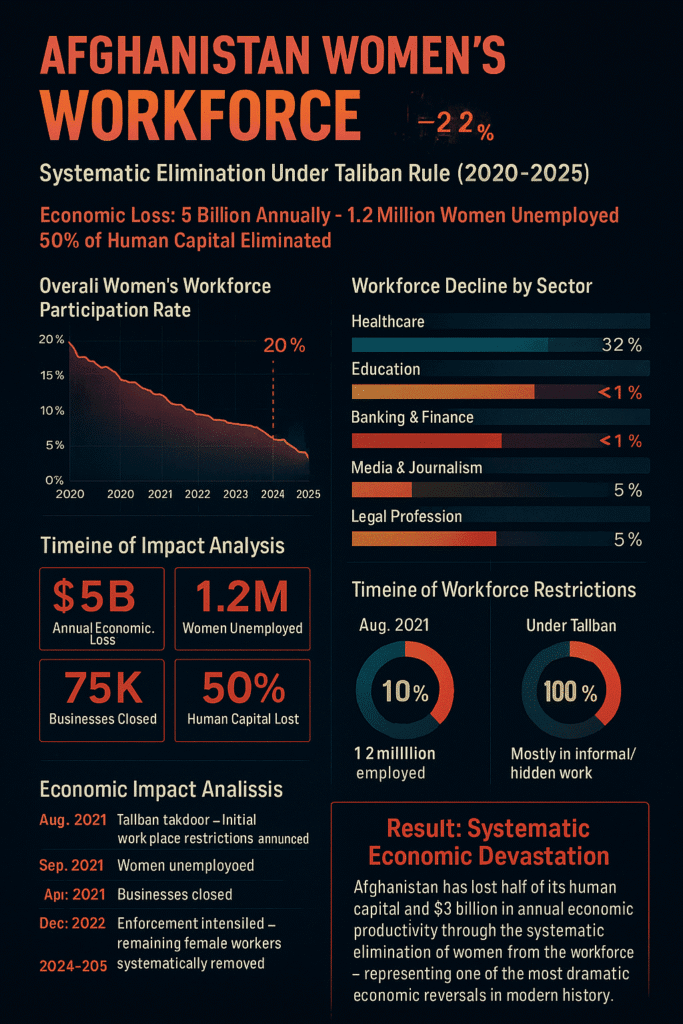

The economic impact of political monopoly extends far beyond traditional measures of GDP or trade volumes—it represents the destruction of human potential, particularly for women who once contributed significantly to Afghanistan’s economy.

Before Taliban rule, women comprised approximately 20% of Afghanistan’s workforce and contributed an estimated $5 billion annually to the economy. The elimination of women from most economic sectors hasn’t just created hardship for individual families; it has fundamentally altered Afghanistan’s financial structure. Industries like healthcare, education, and banking, which relied heavily on female participation, have been crippled.

Foreign investment has virtually disappeared, not just because of sanctions, but because the elimination of political opposition creates unpredictable governance. Investors need stable institutions and the rule of law—concepts that become meaningless when a single organisation holds absolute power without checks or balances.

The brain drain has been devastating and deeply personal. I know talented Afghan women who have fled to countries around the world, taking with them skills, knowledge, and dreams that Afghanistan desperately needs. When Mariam, a former colleague who was a brilliant economist, tells me about her new life as a refugee in Germany, I feel both happy for her safety and heartbroken for what Afghanistan has lost.

Challenges in the banking sector have disproportionately affected women. Female-owned businesses, which once numbered in the tens of thousands, have been forced to close not just because of direct restrictions, but because women can no longer access banking services independently. The ripple effects touch every aspect of economic life.

International aid distribution has become increasingly complicated, lacking effective political oversight. Aid organisations struggle to ensure resources reach those most in need when there are no independent political voices to advocate for marginalised communities or monitor government distribution.

Human Rights Implications Under Political Monopoly

The human rights implications of Afghanistan’s political party bans cannot be separated from the broader assault on fundamental freedoms. Still, they create a particularly insidious form of oppression because they eliminate the very mechanisms through which human rights are typically protected and advanced.

Political prisoners in Afghanistan today include not just former government officials, but women who dared to protest publicly, journalists who covered opposition voices, and civil society activists who organised peaceful demonstrations. The cases that keep me awake at night are often of women like Tamana Zaryabi Paryani and Parwana Ibrahimkhel, who were arrested during women’s protests and simply disappeared. Without political opposition to demand accountability, these cases fade into the shadows.

Freedom of assembly and association has been eliminated not through complex legal frameworks, but through simple prohibition backed by force. When women gathered to protest the closure of girls’ schools, they weren’t engaging in political party activities—they were exercising fundamental human rights. Yet the absence of any legitimate political opposition meant their voices had no institutional channels through which to be heard.

Minority rights have been particularly impacted because political parties often served as vehicles for ethnic and religious minorities to participate in governance. The Hazara community, which faced discrimination even under previous governments, now has no political representation whatsoever. Women from minority communities face double discrimination—first as women, then as members of ethnic or religious minorities.

International human rights monitoring has become nearly impossible without local political organisations to provide information and access. Human rights organisations that once partnered with political parties to document abuses now work independently, making comprehensive monitoring extremely challenging.

Regional Security and Geopolitical Implications

Afghanistan’s political monopoly has created security challenges that extend far beyond its borders, with implications that are particularly concerning for women’s rights movements across the region.

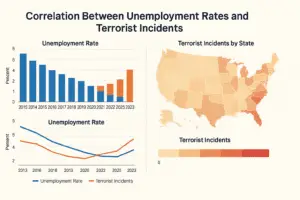

The elimination of political opposition has created a governance vacuum that terrorist organisations have attempted to fill. ISIS-K continues to operate in Afghanistan, exploiting the absence of diverse political voices that might have provided alternative pathways for grievance resolution. When people have no legitimate political outlets, extremism becomes more attractive.

Cross-border political movements have been significantly impacted. Afghan women refugees in Pakistan, Iran, and other neighbouring countries often struggle to organise politically because they lack connections to legitimate opposition movements within Afghanistan. This isolation makes it harder to maintain pressure for political reform and women’s rights.

The Taliban’s relationships with neighbouring countries’ political systems have become increasingly important as regional powers must decide how to engage with a government that has eliminated political pluralism. This creates a troubling precedent where authoritarian governance models appear to be accepted by the international community when convenient.

Counter-terrorism efforts have been complicated by the absence of political opposition that might have provided intelligence and local knowledge about extremist groups. Traditional counter-terrorism approaches often rely on diverse political networks to identify and isolate radical elements—networks that no longer exist in Afghanistan.

Regional powers face a strategic dilemma: engaging with the Taliban risks legitimising their elimination of political opposition, but isolation might push Afghanistan toward even more radical positions. From a women’s rights perspective, this calculus is particularly frustrating because regional powers often prioritise security and economic interests over human rights concerns.

Future Prospects and Potential Scenarios

Looking toward the future of Afghanistan under Taliban rule, I find myself oscillating between despair and cautious hope. The sustainability of complete political monopoly faces several challenges that could create openings for change, though the timeline remains deeply uncertain.

Internal Taliban faction dynamics present the most immediate possibility for political evolution. While the movement presents a unified front publicly, there are known tensions between pragmatists who favour some international engagement and hardliners who reject any compromise on their interpretation of Islamic governance. These tensions could eventually create space for limited political pluralism, though likely not in forms that would satisfy international human rights standards.

The economic crisis facing Afghanistan creates pressure for political reform that the Taliban cannot ignore indefinitely. A government that cannot provide basic services or economic opportunities for its population faces legitimacy challenges, even when opposition is banned. However, the Taliban has shown remarkable resilience in maintaining power despite financial hardship.

Civil resistance movements, particularly those led by women, continue to operate underground despite the enormous risks they face. Every time Afghan women gather privately to read books, teach girls, or organise support networks, they are engaging in political acts that challenge the Taliban’s authority. These movements may not constitute traditional political opposition, but they represent forms of resistance that could eventually coalesce into larger political challenges.

International pressure points for political reform include Afghanistan’s desire for global recognition, access to frozen assets, and participation in regional economic initiatives. However, the Taliban has shown a willingness to endure significant economic hardship rather than compromise on their political model.

The long-term sustainability of single-party governance in Afghanistan faces several structural challenges. Young Afghans who have been exposed to democratic ideals may prove unwilling to accept permanent political exclusion. Women, who comprise half the population but are entirely excluded from governance, represent a massive source of potential opposition. Economic development requires diverse perspectives and skills that are difficult to maintain under a rigid political monopoly.

However, I must be realistic about the timeline for change. The Taliban has demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of power consolidation, and they have learned from the mistakes of their previous rule. They have systematically eliminated not just political opposition, but the social and economic foundations that might support future opposition movements.

Conclusion

Afghanistan under Taliban rule represents one of the most complete political transformations of the 21st century, with the systematic elimination of political parties creating a governance vacuum that extends far beyond Afghanistan’s borders. As a woman watching this unfold, I am struck not just by the political implications but by the profound human cost of eliminating half the population from any meaningful participation in their country’s governance.

The political party bans have not only reshaped internal power structures but have also isolated Afghanistan diplomatically and economically from much of the international community. More importantly, they have created a system where the voices, experiences, and perspectives of women and minorities are not just marginalised—they are entirely absent from decision-making processes that affect every aspect of daily life.

As we move forward in 2025, the sustainability of this political monopoly remains questionable, but the timeline for change is heartbreakingly uncertain. While the Taliban has consolidated power effectively, the absence of legitimate political opposition has created underlying tensions that could potentially destabilise the region. The international community continues to grapple with how to engage with a government that has eliminated fundamental democratic principles while addressing the humanitarian needs of the Afghan people.

What keeps me going is the knowledge that Afghan women have not been defeated, merely silenced temporarily. In homes, in private gatherings, in quiet acts of resistance, the spirit of political engagement survives.

Understanding these political dynamics is crucial for policymakers, researchers, and anyone seeking to comprehend the complex realities of modern Afghanistan and its impact on global stability. But more than that, it is essential for ensuring that when the opportunity for political change does arise, the international community is prepared to support the full participation of all Afghans, including the women who have paid such a devastating price for the Taliban’s political monopoly.

The story of Afghanistan’s political transformation is still being written. As a woman committed to justice and human rights, no system of governance that excludes half the population can ultimately succeed. The question is not whether change will come, but when, and whether the international community will be ready to support a genuinely inclusive political future for Afghanistan.

Smart bankroll management is key, even with exciting platforms like maya games link. Verification steps, like those on Maya Games, are crucial for secure play-always prioritize responsible gaming! It’s easy to get carried away.

Looking for some Melbet promo codes? Melbetcodepromo could be a good place to start. I’m interested myself to use these to my advantage! Check it out: melbetcodepromo

Hey, gotta mention 68boss. I signed up, and it delivered pretty neat experiences. I was surprised by their customer service, actually helpful. Check it out: 68boss.

Okay, been checking out BetBoomCasino lately. Pretty decent selection of games, ya know? Slots are fun and they’ve got a live dealer section that keeps things interesting. Could use a little more variety in the promos, but overall, not bad. Check it out here betboomcasino.

Been playing on sv88 for a bit. Their live dealer games are pretty awesome, great graphics too. Definitely recommend giving it a shot if you’re into that. Try it out at sv88. Cheers!