Table of Contents

Where Do the Funds Come From?

Here’s something that keeps me up at night: terrorist groups don’t just magically appear with weapons and resources. They need money, and lots of it. The funding sources are way more complex than most people realize.

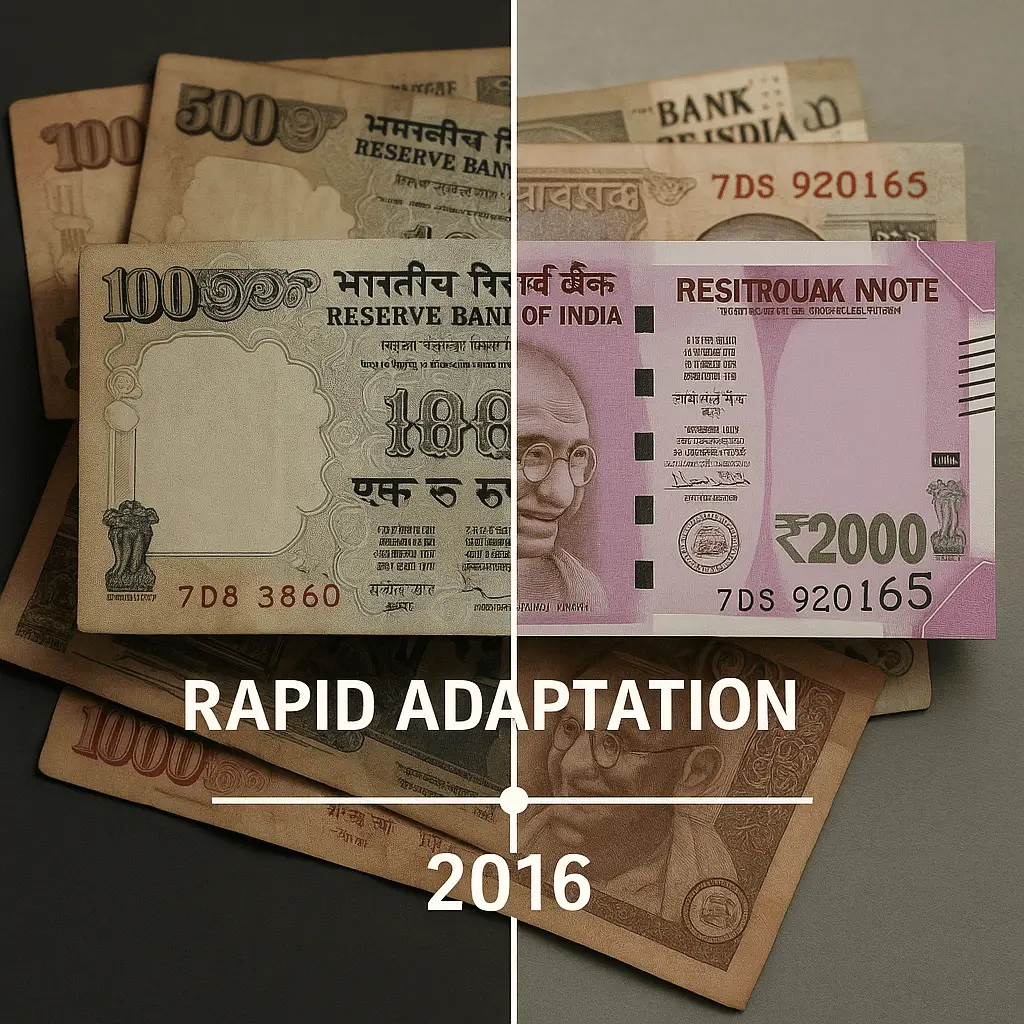

I remember being shocked when I learned that the day after India’s demonetization policy in 2016, terrorists were caught with brand new Rs. 2000 notes. Think about that – within 24 hours, these groups had adapted to a major economic policy change. That’s not amateur hour; that’s sophisticated financial networking.

The reality is brutal but simple: terrorism operates like any other business. They need cash flow, supply chains, and financial infrastructure. Some of this comes from obvious sources like drug trafficking, kidnapping for ransom, and extortion. But here’s where it gets really dark – governments sometimes fund these groups themselves.

Yeah, you heard that right. States will covertly support militant organizations to destabilize their rivals or maintain geopolitical advantage. It’s like a deadly chess game where innocent people are the pawns.

As former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan put it perfectly: “Terrorism is the ultimate perversion of political struggle, funded often by economic interests hidden in plain sight.”

Modern terrorist financing has also embraced technology. Cryptocurrency transactions, informal money transfer systems like hawala, and even legitimate businesses serve as fronts. The 2008 Mumbai attacks, for instance, inflicted hundreds of millions in economic losses and showed how a relatively small investment in terror can create massive economic disruption.

The scariest part? These financial networks adapt faster than our systems to stop them.

Poverty, Discrimination, and Economic Inequality: The Breeding Grounds of Terrorism

This is where the conversation gets uncomfortable, but we need to have it. Terrorism doesn’t happen in a vacuum – it grows in specific conditions, and those conditions are usually economic.

I’ve spent years studying data from the Global Terrorism Database and World Bank, and the pattern is crystal clear: areas with high unemployment, poverty, and discrimination see way more terrorist incidents. It’s not a coincidence.

The UNDP puts it bluntly: “exclusion and inequality are among the main drivers of radicalization and violence.” When people feel like the system has abandoned them, when they can’t feed their families or see a future for their kids, extremist groups start looking like the only option.

Here’s what really frustrates me about this: we know economic sanctions are supposed to weaken state-sponsored terrorism, but they often backfire. Instead of hurting the bad guys, sanctions increase hardship for regular people, creating more resentment and pushing more individuals toward extremism.

I’ve seen this pattern repeat itself across different regions. Young men in particular – when they’re unemployed, discriminated against because of their religion or ethnicity, and watching their communities suffer – become prime targets for recruitment.

It’s not that poverty automatically creates terrorists. Plenty of poor communities never turn to violence. But when you combine economic desperation with political exclusion and social discrimination, you get a toxic mix that extremist groups know exactly how to exploit.

As economist Amartya Sen explains it: “Poverty alone does not breed terrorism, but it is the lack of freedoms, injustice, and inequality that ferment violence.”

The solution isn’t just throwing money at the problem – it’s about creating genuine opportunities and addressing systemic injustices.

The Cost of Terrorism: Human Tragedy and Economic Fallout

Let me be clear about something: the real cost of terrorism goes way beyond the immediate violence we see on the news. The economic ripple effects can devastate entire regions for years.

I’ve tracked the aftermath of major terrorist attacks, and the pattern is always the same. First, there’s the obvious human cost – families destroyed, communities traumatized, lives cut short. That’s the part that makes headlines.

But then comes the economic tsunami. Property and infrastructure get destroyed, sometimes costing millions of dollars to rebuild. Foreign investment dries up because nobody wants to put money into unstable regions. Tourism collapses overnight – and for many developing countries, that’s a major source of income.

The 2008 Mumbai attacks are a perfect example. Beyond the 166 people killed and hundreds injured, the economic losses reached hundreds of millions of dollars. Hotels, restaurants, and local businesses suffered for years afterward. International companies pulled out or delayed investments. The entire hospitality industry in Mumbai took a massive hit.

Governments then have to divert huge chunks of their budgets to security measures. Money that could have gone to schools, hospitals, or infrastructure development instead gets spent on counter-terrorism operations, border security, and surveillance systems.

Here’s the cruel irony: the very economic hardship caused by terrorism often creates conditions that breed more terrorism. It’s a vicious cycle that’s incredibly hard to break.

I’ve calculated that for every dollar spent on a terrorist attack, the economic damage can be hundreds or thousands of times greater. It’s asymmetric warfare at its most effective – small investments in violence creating massive economic disruption.

This is why addressing terrorism’s root causes isn’t just morally right – it’s economically essential.

Government’s Double Role: Combating and Funding Terrorism

This might be the most disturbing part of the whole terrorism-economics relationship: governments playing both sides of the game.

On one hand, we see states implementing economic sanctions, freezing assets, and creating complex regulatory frameworks to disrupt terrorist financing. The international community spends billions on counter-terrorism efforts, financial monitoring systems, and intelligence sharing.

But here’s the part that makes my blood boil: some of these same governments are secretly funding militant groups when it serves their strategic interests. They’ll use proxy forces to destabilize rival nations or maintain influence in contested regions.

It’s like watching someone call the fire department while secretly starting fires in their neighbor’s backyard.

The sophistication of modern terrorist financing has forced everyone to step up their game. Cryptocurrency transactions are harder to trace than traditional banking. Informal money transfer systems like hawala operate outside conventional financial institutions. Legitimate businesses get used as fronts for moving money across borders.

International cooperation becomes absolutely critical, but it’s often undermined by these conflicting interests. How can you have effective counter-terrorism financing efforts when some of the participants are secretly part of the problem?

The regulatory frameworks we’ve built are impressive on paper – tracking suspicious transactions, monitoring international transfers, coordinating between intelligence agencies. But they’re only as strong as the political will to enforce them consistently.

What frustrates me most is that regular citizens pay the price for these geopolitical games. Families get caught in economic sanctions meant to target terrorists. Small businesses struggle with increased compliance costs. Meanwhile, the actual bad actors find new ways to move money around the system.

Transparency and accountability aren’t just nice ideals – they’re practical necessities for any serious counter-terrorism effort.

The Solution: Ending Terrorism Starts with Ending Its Practice

Okay, here’s where I get passionate, because I genuinely believe we can solve this problem – but only if we’re willing to address the real root causes instead of just treating symptoms.

Military action and police operations are necessary, don’t get me wrong. But they’re not sufficient. We need systemic change that tackles the economic and social conditions that make terrorism attractive in the first place.

First, we absolutely must reduce economic inequality. That means creating real jobs and opportunities for marginalized communities. Not charity, not handouts, but genuine economic participation. When young people have legitimate paths to success, extremist recruitment becomes much harder.

Second, inclusive governance isn’t optional anymore. Governments need to respect diversity of religion, ethnicity, and background. When people feel represented and heard through legitimate political processes, they’re less likely to turn to violence.

Third, we need much stronger international cooperation to disrupt terrorist financing. That means serious consequences for states that play both sides, better coordination between financial institutions, and closing the loopholes that allow money to flow to terrorist organizations.

But here’s the most important part: we need to reject violence and extremism at every level, from grassroots activism to political leadership. That includes state-sponsored terrorism, proxy wars, and the whole cynical game of funding militant groups for strategic advantage.

As Nelson Mandela said, “No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love.”

The solution isn’t pointing fingers or playing blame games. It’s collective action to stop practicing terrorism in all its forms – including the kinds that governments don’t want to admit they’re involved in.