Introduction

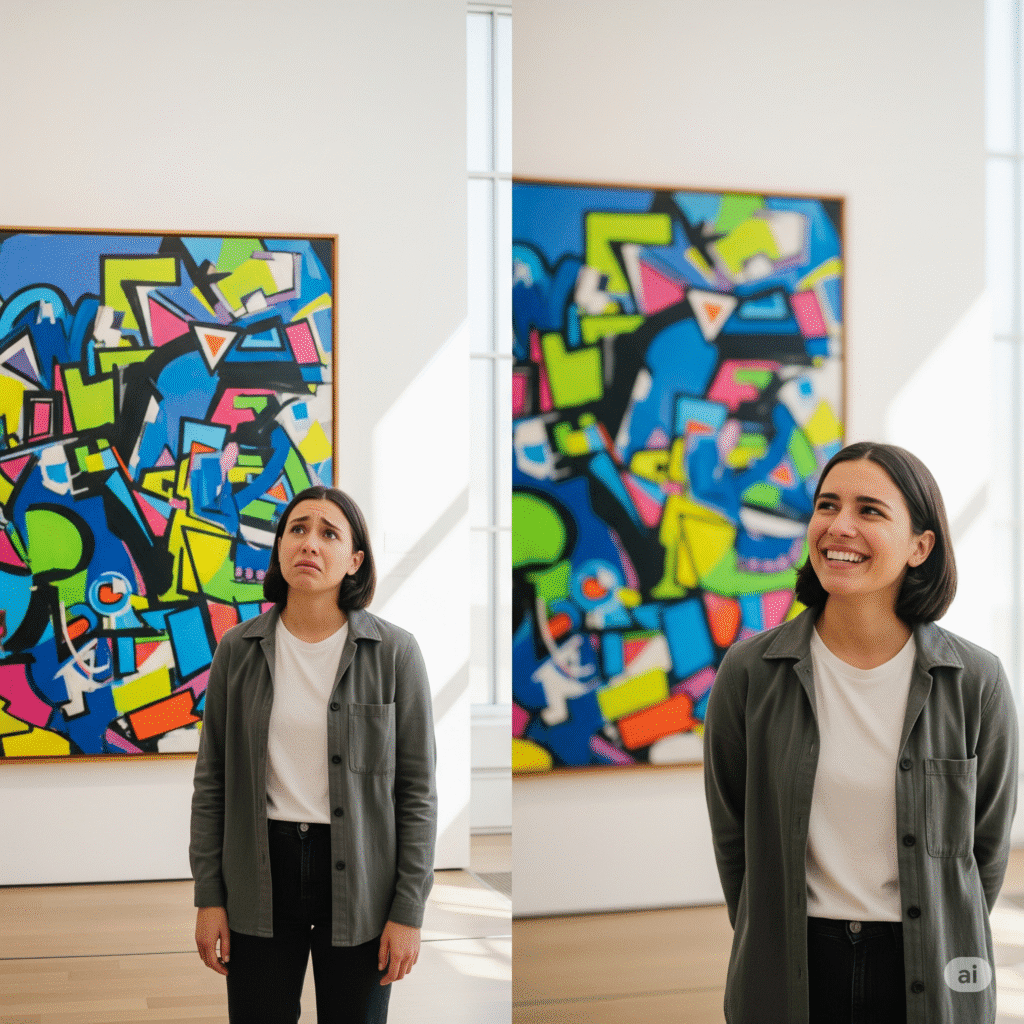

Have you ever walked into a modern art museum, stared at a canvas covered in random paint splatters, and thought “My five-year-old could do that”? Trust me, you’re not alone! About 68% of museum visitors admit they feel confused or intimidated by contemporary art, according to recent surveys.

I used to be one of those people who’d nod politely at abstract paintings while secretly wondering if the whole art world was playing some elaborate joke on the rest of us. But here’s the thing – once you understand the stories behind these movements and what the artists were actually trying to say, modern art becomes incredibly fascinating!

After spending years studying art history and visiting countless galleries, I’ve learned that modern art isn’t trying to trick you or make you feel stupid. These movements emerged from real human experiences – wars, social upheaval, technological breakthroughs, and personal struggles. Every seemingly “weird” artwork has a story worth understanding.

Let’s break down the most important contemporary art movements in simple terms, so you can walk into any gallery with confidence instead of confusion!

What Exactly Is Modern Art?

Okay, let’s clear up some confusion right from the start because this trips up almost everyone I talk to about art. “Modern art” and “contemporary art” aren’t actually the same thing, even though people use these terms interchangeably all the time.

Modern art technically refers to artistic movements from roughly the 1860s to the 1970s. We’re talking about Impressionism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism – all those movements that broke away from traditional realistic painting. Contemporary art is what’s happening now, from the 1970s onward.

But here’s where it gets confusing: most people say “modern art” when they really mean “art that looks weird or different from classical paintings.” I’ve given up trying to correct everyone because honestly, the distinction isn’t that important unless you’re writing an art history paper!

What matters is understanding that these artistic movements didn’t happen in a vacuum. Each one was responding to something specific happening in the world. The Impressionists were reacting to photography making realistic painting less necessary. Abstract Expressionists were processing the trauma of World War II. Pop artists were commenting on consumer culture and mass media.

Abstract Expressionism: America’s First Major Art Movement

Abstract Expressionism was basically America’s declaration of independence from European art dominance, and honestly, it’s one of my favorite movements to study because the artists were such fascinating, tortured characters.

This movement emerged in New York in the 1940s and 1950s, right after World War II. American artists were tired of European art setting all the trends, and they wanted to create something uniquely American. The timing was perfect because many European artists had fled to New York during the war, bringing new ideas and energy.

Jackson Pollock is probably the most famous Abstract Expressionist, and his story is both inspiring and tragic. I remember the first time I saw one of his drip paintings in person – it was completely different from seeing it in a book. The scale, the texture, the way the paint builds up in layers – you can actually feel the physical energy he put into creating it.

Pollock’s technique wasn’t random chaos, despite what it looks like. He developed a specific method of dripping and pouring paint that allowed him to work from all sides of the canvas. He said he wanted to be “in” the painting, not just standing outside it painting. It was revolutionary because it made the act of painting itself part of the artwork.

Mark Rothko took a completely different approach with his color field paintings. Those huge canvases with blocks of color might look simple, but they’re incredibly sophisticated. Rothko wanted viewers to have spiritual, emotional experiences with his paintings. He spent years perfecting his layering techniques to create colors that seemed to glow from within.

Willem de Kooning painted these aggressive, distorted figures that made people uncomfortable. His “Woman” series caused a huge controversy because the female figures were so violent and disturbing. But de Kooning was exploring the complexity of human relationships and emotions in ways that pretty, idealized paintings never could.

Abstract Expressionism gave American artists permission to be messy, emotional, and experimental. It proved that art didn’t have to be beautiful or pleasant to be meaningful. This movement laid the groundwork for everything that came after.

Pop Art: When High Art Met Consumer Culture

Pop Art might be the most misunderstood movement in modern art history. People see Andy Warhol’s soup cans or Roy Lichtenstein’s comic book paintings and think “That’s not art, that’s just copying commercial images!” But that’s exactly the point – and it was revolutionary.

The movement emerged in the 1950s and exploded in the 1960s as a direct response to Abstract Expressionism’s serious, emotional approach. Pop artists were saying “Why should art be separate from everyday life? Why can’t we make art about the things people actually see and use every day?”

Andy Warhol was the master of this philosophy. I used to think his Campbell’s Soup Cans were just a gimmick until I learned the story behind them. Warhol ate Campbell’s soup for lunch every day for 20 years – it was his personal connection to mass-produced consumer culture. By painting something so ordinary and repetitive, he was commenting on how mass production was changing human experience.

His screen printing technique was just as important as his subject matter. Instead of painting by hand, Warhol used mechanical reproduction methods that mimicked commercial printing. This challenged the idea that art had to be unique, handmade objects. Why shouldn’t art be mass-produced like everything else in modern life?

Roy Lichtenstein’s comic book paintings look simple, but they required incredible technical skill. He hand-painted every single Ben-Day dot to perfectly mimic the printing process used in comic books. He was elevating “low” commercial art to “high” art gallery status, questioning why we make these distinctions in the first place.

Minimalism: Less Is More (And More Difficult Than It Looks)

Minimalism is probably the movement that causes the most “my kid could do that” reactions, but trust me, it’s way more complex than it appears. I spent years dismissing minimalist art until I really started studying it, and now I’m fascinated by how much meaning can be packed into such simple forms.

The movement developed in the 1960s as a reaction against Abstract Expressionism’s emotional intensity and Pop Art’s commercial imagery. Minimalist artists wanted to strip away everything unnecessary and focus on pure form, space, and materials. They were influenced by industrial manufacturing and Eastern philosophy.

Donald Judd’s metal boxes might look like they belong in a warehouse, not a museum. But Judd was exploring how we perceive space and objects. Each box is precisely manufactured to specific measurements, and the way they’re arranged in space creates relationships between the objects and the room itself. The art isn’t just the boxes – it’s your experience of moving around them.

Dan Flavin used nothing but fluorescent light tubes to create his sculptures. When I first encountered his work, I thought it was a joke. But then I spent time in a room filled with his colored light installations, and I understood what he was doing. The light changes how you see the entire space, and even changes how you feel physically. It’s minimalist, but the effect is incredibly powerful.

Conceptual Art: When Ideas Matter More Than Objects

Conceptual art is where a lot of people completely lose patience with contemporary art, and I get it. When the “artwork” is just a written instruction or a performed action, it can feel like the artist is being deliberately difficult. But once you understand what conceptual artists were trying to accomplish, it opens up completely new ways of thinking about art.

The movement emerged in the 1960s when artists started questioning fundamental assumptions about what art could be. Why does art have to be a physical object? Why does it have to be beautiful? Why does it have to last forever? These artists were more interested in ideas than in making things you could hang on a wall.

Marcel Duchamp was the grandfather of conceptual art, even though he was working decades earlier. His “Fountain” – a urinal signed “R. Mutt” and placed in an art exhibition – asked the most basic question: What makes something art? Is it the object itself, the artist’s intention, or the context where it’s displayed?

Installation Art: Creating Environments That Transform Spaces

Installation art is where contemporary art gets really immersive and experiential. Instead of making objects to look at, installation artists create entire environments that you walk through and experience with your whole body. It’s probably the most accessible form of contemporary art because it’s so visceral and immediate.

The medium really took off in the 1970s when artists started getting interested in site-specific work and environmental concerns. Instead of making portable objects that could be sold and moved around, installation artists create works that are designed for specific spaces and often can’t exist anywhere else.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s massive environmental projects are some of the most spectacular examples of installation art. When they wrapped the Reichstag in Berlin or created 7,503 saffron gates in Central Park, they weren’t just making pretty decorations. They were changing how people experienced familiar spaces and raising questions about ownership, permanence, and the relationship between art and environment.

Digital and New Media Art: Art in the Internet Age

Digital art is where contemporary art meets technology, and it’s evolving so fast that what was cutting-edge five years ago already looks dated. This is the most dynamic and unpredictable area of contemporary art right now, and it’s forcing us to rethink fundamental questions about what art can be and how it exists.

The medium started emerging in the 1960s when artists got access to early computers, but it really exploded with the internet and personal computers in the 1990s. Now we’re dealing with everything from virtual reality installations to blockchain-based NFT art to AI-generated images.

Street Art and Graffiti: From Vandalism to Gallery Walls

Street art’s journey from illegal vandalism to internationally recognized art form is one of the most fascinating developments in contemporary culture. I’ve watched this transformation happen over the past few decades, and it raises important questions about who gets to decide what counts as legitimate art.

Graffiti culture emerged in New York in the 1960s and 1970s, primarily in marginalized communities. Early graffiti writers like TAKI 183 and Cornbread weren’t thinking about making art – they were marking territory, building reputations, and creating identity in urban environments that often ignored them.

How to Approach and Appreciate Contemporary Art

After years of studying and experiencing contemporary art, I’ve developed some strategies that help me approach unfamiliar or challenging artworks. The key is to stay curious rather than judgmental, and to remember that confusion is often the starting point for understanding.

The first thing I always tell people is to spend time with artworks. Our culture trains us to consume images quickly, but contemporary art often rewards slow, careful attention. I’ve had experiences where a piece that seemed boring or incomprehensible at first glance revealed layers of meaning after I spent 10 or 15 minutes really looking at it.

Read the wall text, but don’t let it completely determine your experience. Gallery labels can provide helpful context about the artist’s intentions and the historical background of the work. But your personal response to the artwork is just as valid as the curator’s interpretation.

Conclusion

Understanding contemporary art movements isn’t about memorizing names and dates – it’s about developing new ways of seeing and thinking about the world around us. Each movement we’ve explored emerged from specific cultural moments and human experiences that are still relevant today.

The beauty of contemporary art is that it’s constantly evolving and responding to current issues. Climate change, social media, artificial intelligence, global migration – today’s artists are processing these challenges and creating works that help us understand our contemporary moment.

I’ve learned that the most rewarding approach to contemporary art is to stay curious and open-minded. Every “weird” artwork has a story behind it, and understanding those stories has enriched my understanding of both art and culture. The Abstract Expressionists’ search for American artistic identity, Pop Art’s critique of consumer culture, Conceptual Art’s questioning of assumptions – these aren’t abstract art history topics, they’re explorations of what it means to be human in the modern world.

Don’t worry if you don’t immediately “get” every piece of contemporary art you encounter. The goal isn’t to become an expert who can impress people at gallery openings. The goal is to develop your own relationship with visual culture and to use art as a tool for thinking about your own experience and the world you live in.

The next time you visit a contemporary art museum, try approaching it like an adventure rather than a test. Let yourself be surprised, confused, delighted, or even annoyed. These reactions are all part of the experience, and they’re often the beginning of deeper understanding.

What contemporary art movement or artist has surprised you the most? Have you had any “aha” moments where a piece of art suddenly made sense in a new way? I’d love to hear about your experiences with contemporary art in the comments below – sometimes the best insights come from fresh perspectives!